Prologue

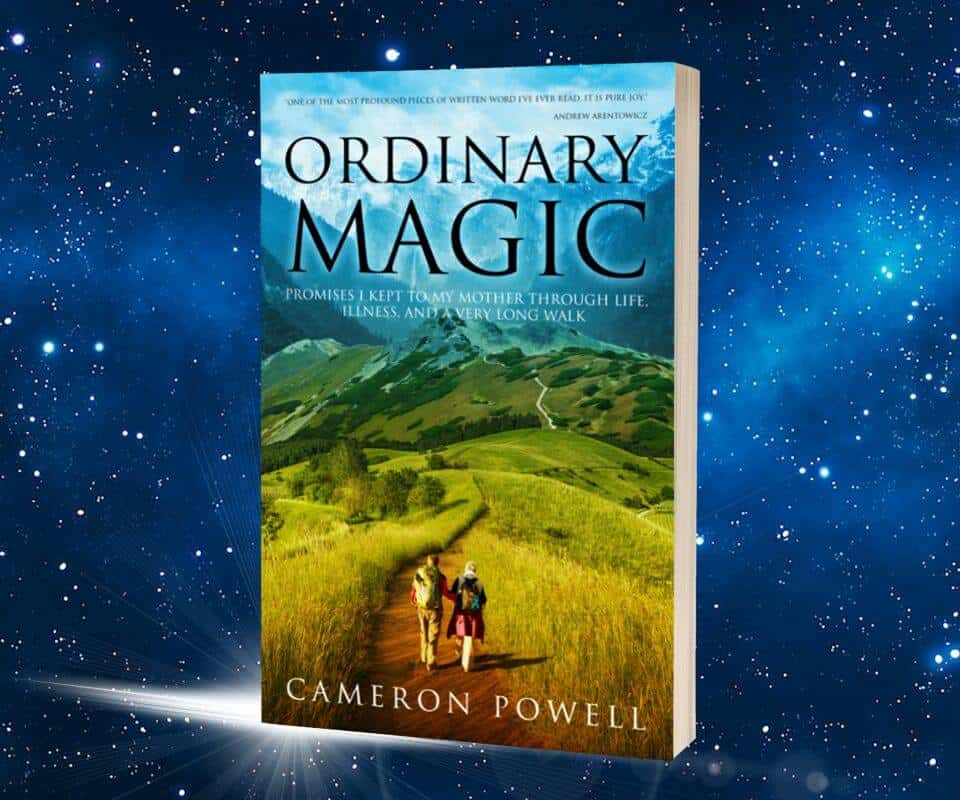

Ordinary Magic

"One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things.” – Henry Miller

I was married once, and with a brevity I was surprised to find agreeable. The nature channels tell me penguins can boast of longer relationships, and all too often do. By the time a judge closed the file, in the fall of 2011, I stood with my mother – who’d had no happy unions herself – on a yellow-arrowed path, six thousand miles away, like characters in some 21st century update to the Wizard of Oz. The wind whipped at the cup on her backpack. I reached out to stuff it into a pocket.

My sixty-seven-year-old mother was on this five-hundred-mile trail because she wanted a cure for her ovarian cancer – or at least a break from worrying about “all the cutting and poison”, as she put it. She had beaten back cancer in 2001, aged 57, ditched the emperor of all maladies in a fiery lake of chemotherapy and then ran and ran and would not look back. Oh, the places I went! she would write later, in our blog at CaminoNotChemo.com. Erlangen, Germany, where I was born, Switzerland, Venice, Amsterdam, and more. How my endorphins just went nuts with joy. I felt such a sense of well being, of wonderful peace, that I was in tears half the time. I said prayers of gratefulness and thanks for my eyes that could see the beauty. For my senses that could take it all in and amazement at the miracle that is our planet.

But cancer had returned with reinforcements just over a year ago, in April, 2010, as measured by the cancer antigen test for ovarian cancer, called the CA-125. She was astonished.

“You mean it can come back?”

Surgery, said the surgeons.

Chemo, quoth the chemotherapists.

Radiation, recommended the radiators.

She felt besieged with choices and their risks: another chemo, or death sometime soon -- which was worse? Her first rodeo with chemo almost a decade earlier had been so excruciating that she cried whenever the merest idea of enduring it again came up. Besides, she felt fine. She was still not symptomatic, and her cancer was unusually slow-growing. “Not yet,” Mom had told the doctors. “I want to do it my way first.” Though Doc, her primary care physician, would have preferred she do something immediately, he and several other doctors agreed there was no immediate need to resort to the extreme measure of the treatment born of mustard gas. That was over a year ago. So now here we were, with backpacks and hiking poles, crippling blisters (her) and a torn calf (me), high on the wild-dog-infested and wind-swept spine of a mountain range in northern Spain.

Exhausted from the long road to divorce, I hadn’t believed there were any answers for me here, so I had sort of convinced myself I wanted nothing. I stood at the foot of a high rubbled mound, holding my new Nikon SLR, which I’d rationalized buying, from Costco, for this very trip. The video was on: Mom had talked about this moment for months, and I am nothing if not a catcher, or perhaps I mean a chaser, of moments. She was picking her way up the mound, through the powdery rocks, gray and white like her short-cropped hair. Cousin Carrie, 15, had abandoned her own, massive backpack and was watching the scene from my left. In a field to my right an older man, very tall, sturdy boots, backpack, was weeping.

The mound was pierced at its summit by a thirty-foot-tall oak post, about as big around as a telephone pole. The very top of the post was fitted with a cross bearing an iron cap, like the sort of hat an English bulldog might wear, if an English bulldog had scored an audience with the Queen. The three free arms of the tiny iron cross ended in fleurs-de-lis.

For thousands of years a mound of rocks has marked the summit of this mountain range. And for thousands of years, some version of the Cruz de Ferro has spied on the most intimate rites of countless pilgrims – first Celts and other Pagans, later just Catholics, now we pagans were back – as they formed meaning out of this very way station. A million pilgrims before us, along with shamans, druids, sundry witches, and Catholic royalty, had built up the mound with hand-placed relics from their own private rituals of letting go: of anger, of grief, of resentment, of illness – letting go, perhaps, even of the fear of death. Because that is what people do on pilgrimages, of any kind, whether they mean to or not. They let go. That’s what the verb to forgive means. To forgive others, and, harder yet, to forgive oneself. In his brief life, Jesus told us what he knew about forgiving our neighbors and our enemies alike, but the bastards killed him before he could show us how to forgive ourselves.

An ancient tradition holds that pilgrims should bring to the Cruz, from their own homes, one small stone and one personal item, and to leave them both behind at the Cross. I watched my mother: her newly short hair, her glasses on a red string. She was placing among the rocks a small stone she’d carried from a deep and ancient canyon near her adopted home in western Colorado. Then she began to search her trekking vest for the personal item she’d stored away for this day.

Previous pilgrims had left behind other, telling things. A tube of lipstick among the rocks. A postcard of Bruges, scrawled in a woman’s hand. Folded pieces of paper and fragments of words in Spanish and English, German and Dutch, Korean and Basque. Underwear that raised certain questions. A Matchbox car that looked to my inner-nine-year-old’s eye like a ’68 Corvette. A toy soldier with only one leg, and the half-eaten cookie on which he had been subsisting among the rubble. A German pilgrim had erected a small German flag among the rocks. Not to be outdone, so had a Belgian. Or vice versa, let’s not start another war. The lower third of the cross itself was also littered with splashes of color and texture. I could make out a tacked-up orange baseball cap and a clip-less biking pedal, a black-and-white photo of a European peasant family, circa 1930s, a 1970s photo of a boy, in a white shirt with blue stripes, holding a Bible.

I hadn’t brought anything, and I would not leave anything.

My mother, still with her back to Carrie and me, stood now at the top of the mound. The Iron Cross loomed over her, stout in the gathering wind. She kneeled amidst the murmuring shades of the druids, she bowed her head. She cupped her offering with both hands and held it over her head, a modest proposal to the cosmos about what she should be allowed to let go of. When I saw her shoulders start to shake I began to cry, too, but quietly and with minimal shaking, because I was the expedition videographer, not to mention its chief biographer, photographer, legal counsel, and acting podiatrist.

I handed the camera to Carrie and went to join my mother.

Ready for the rest of the story?

Sign up below and choose your preferences.